Science and The Pursuit of Knowledge: Part I

Have you ever gotten into a debate over a scientific topic with someone? For example, Big Bang Theory or Evolutionary Theory? If you have, maybe it went something like this, “We know the Big Bang happened because we have evidence of space expanding via Hubble’s Law, and the Cosmic Microwave Background suggests that at one time everything was condensed into a very small volume before rapid expansion.” In my experience, the people I debate respond by either questioning the method of observing these two phenomena, or more often, they call into question whether this evidence is enough to justify belief in the Big Bang (aka. “It isn’t proven”).

They might ask whether there is some other explanation for the observations, or they might suggest that the universe was made yesterday and these observations are “planted” as a distraction from the truth by some cosmic entity. If they respond in the latter, questioning the justification of your belief, they aren’t attacking the science itself. Rather, they are attacking the epistemological underpinning of knowledge and rational belief.

To say that science has proven the Big Bang Theory is, in a sense, to say that we have certainty or knowledge of the Big Bang Theory. What does it mean to have knowledge? We often take the concept of knowledge for granted. If I wanted to know the weather currently, I could walk outside and make an observation. If the sun were out, I would know that the sun is shining by virtue of my observation. Something about my observation and the actual state of affairs forms what knowledge is, but if you were asked to give criteria for how we can know that we know something, what would that criteria consist of?

What is Knowledge?

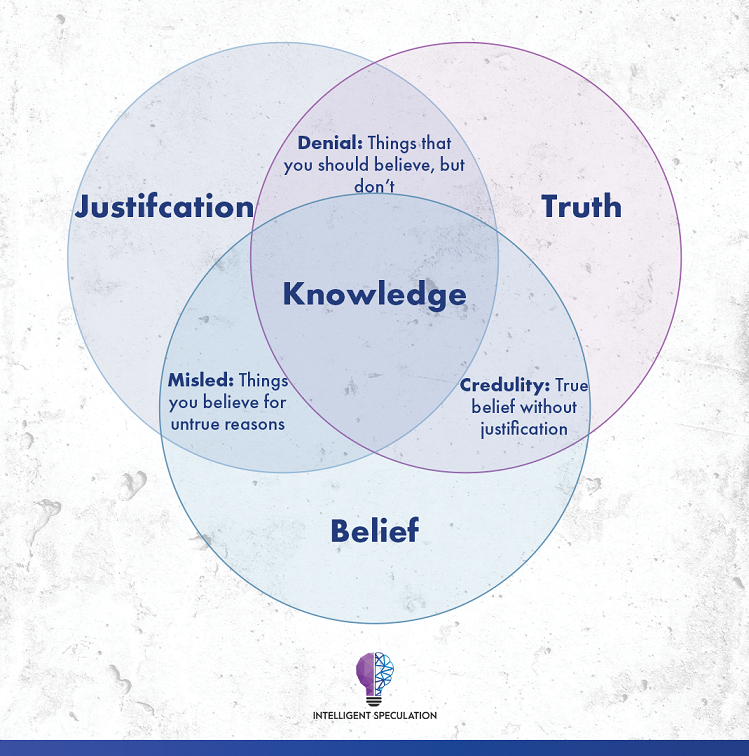

One of the foundational interpretations of what knowledge consists of is called the Justified True Belief (JTB) Theory - this is also called Tripartite Theory of Knowledge. JTB states that a person has knowledge of a proposition, P, if and only if P is True, the person Believes P, and the person is Justified in their belief of P [1]. Circling back to my example with the weather, I went outside and observed that the sun is shining. The proposition, “The sun is shining,” is true. My belief in the proposition is justified based on my observation, and consequentially I also believe that the sun is indeed shining. Next, let’s look at why these three criteria are necessary according to the JTB theory.

The first component is truth. Consider the following proposition: Hillary Clinton is the current president of the United States. We can evaluate whether this proposition is true by looking at the current state of affairs in the United States. The proposition has an objective and absolute truth value. Although the term contains the word ‘truth’, what it means is that the proposition is either true or false. One of the most common ways to describe truth value is by using the correspondence theory of truth which states that, “A proposition is true if and only if it corresponds to the facts (if and only if the world is the way the proposition says it is). A proposition is false if and only if it fails to correspond to the facts. [2]”

The proposition in question regarding Hillary Clinton would receive the truth value of false. If I said, “I know that Hillary Clinton is the current president of the United States,” I would be wrong. There is no way to know that a proposition is true if that proposition is false. Alternatively, there is no way to know a proposition is false if that proposition is true.

The second component is belief. Where the previous component, truth, relates to the actual truth value of the proposition, belief relates to the human perception of that truth value. While the proposition, “Hillary Clinton is the current president of the United States,” is false, it is within the realm of possibility that someone could believe that it is true. This simply illustrates that there is a disconnect between what the truth of a proposition is and what we as humans think it is.

In terms of knowledge, imagine if someone were to say, “I know that the ocean is a body of water, but I don’t believe that it’s true.” This would be a very strange thing to say. If you are certain that a proposition is true (the ocean is made of water), how could you also believe that it is false? There is one way that such a sentence could make sense, but that is only in regard to being surprised by the truth value of the proposition. One could say, “I know the Chicago Bears won the Super Bowl, but I don’t believe it,” as a means of conveying surprise rather than genuine disbelief in the proposition itself.

The final component is justification. Justification is the accumulation of facts that support belief in a proposition. This is where a lot of the debate in epistemology arises, because like knowledge, justification seems to require its own criteria for evaluating what constitutes good justification. For example, if I look outside and see that it is overcast, I might conclude that it will rain. There is some justification to my belief that it will rain, but this isn’t enough to know that it actually will rain. There are plenty of days where it is overcast and doesn’t rain at all.

Justification is important for knowledge in the following way: Imagine Bill tells you that he knows a teapot is in orbit around Alpha Centauri. There is currently no evidence to support such a claim, but he is adamant that he knows it is true. Five hundred years later, it is discovered that a teapot is indeed orbiting Alpha Centauri and has been for at least five hundred years. Either Bill had access to some information, and therefore justification, that nobody else had access to or Bill made a wild guess. Generally, the latter is more probable, and we can intuitively conclude that if Bill made a guess then he really didn’t know.

The JTB theory is not without faults, but it does provide a starting point to talking about knowledge. Many of the issues with JTB are highlighted in Gettier Problems, criticisms which were formulated by Edmund Gettier. One such problem could be presented like this: imagine that you have grown up in an area which has numerous dairy farms. Due to growing up here you are very familiar with what a cow looks like. One day you are driving and look out into a field to see a cow. You proclaim, “I know there is a cow in that field, I see it right there!” However, what you see is actually a statue (or a cake, if you have seen the videos of hyper-realistic cakes). In addition, a real cow is in that field but out of sight. So what would JTB say in this case? The proposition, “There is a cow in the field,” is true. You believe that there is a cow in the field. You also have justification, based on what you see, in thinking there is a cow in the field. Yet, the idea that you should know that there really is a cow in the field based on seeing a hyper-realistic cow statue seems counter-intuitive to our idea of knowledge. So we have demonstrated that we can satisfy the three conditions of knowledge without actually attaining knowledge.

The Real and the Anti-Real

At this point you might be wondering, “If JTB is problematic, how can we know anything at all?” The good news is, there have been many responses to JTB to try to fix the holes that Gettier Problems introduce. The bad news is, there is no universal agreement on which theory of knowledge is best. The primary issue with the Gettier Problem previously described is that the justification (seeing a fake cow) was not enough to justify there being a real cow. We can tell that justification is not black and white, but a spectrum [3]. In science we have a process for judging justification via the peer review process. We check and have others recheck the work to make sure we haven’t actually stumbled upon a “fake cow” so to speak. Even so, most scientists generally say we never “prove” anything in science. Part of this reasoning is due to the Problem of Induction, which I wrote about in “Scientific Argumentation,” but it is much deeper than that. We could argue, as Descartes did, that our perceptions alone do not guarantee our reality. That we could be brains in vats or deceived by an evil demon, therefore all propositions about our reality are in doubt. The responses to Descartes’s demon break down into two major camps: realism and anti-realism.

Scientific Realism is the notion that there really is a mind-independent world (i.e., we are not in The Matrix, everything we see is real and not simulated or planted in our minds), therefore when we do science we are gaining knowledge of the real world. The Scientific Anti-Realist would say that we don’t know that the world we perceive is real and not simulated, but we can gain a sort of contingent knowledge of our experiences. For example, the anti-realist would say that the chair I am sitting on is real only insofar as it exists in my experience of reality, whatever type of reality I am experiencing.

One example where realists and anti-realists will disagree is if you ask them, “Is an electron real?” The realist would say that an electron is indeed real. The proposition, “Electrons are real,” is true to the realist because theories of particle physics, they believe, reflect the actual facts of reality. An anti-realist would say that an electron is real, insofar as our concept of the electron helps explain our experience of this reality. Scientific Anti-Realism has multiple subsets, one of the most common among physicists is known as Instrumentalism. Instrumentalism avoids the problem of whether or not we know anything by simply not making knowledge a goal. Rather, the instrumentalist is concerned with the practical application of ideas and propositions. If we ask an instrumentalist whether an electron is real or not, they might just respond by asking, “Does the theory of particle physics, for which an electron is described, provide accurate predictions?” If the answer is yes then that is good enough for the instrumentalist, no need to concern themselves with the burden of absolute knowledge.

Final Thoughts

Although most of us take knowledge for granted, skepticism of knowledge has been a common philosophical notion at least since the ancient Greeks. Xenophanses of Colophon wrote, “And of course the clear and certain truth no man has seen nor will there be anyone who knows about the gods and what I say about all things. For even if, in the best case, one happened to speak just of what has been brought to pass, still he himself would not know. But opinion is allotted to all. [4]”

In 1639, Descartes began writing his Meditations in which he conducted a thought experiment. If he removed every assumption about the world and started with a completely blank slate, how many propositions could he obtain knowledge about? The very first thing he needed to prove was that he, himself, existed. He posited that, even if a demon were deceiving him in order to make him think he were not real, he must exist in order to be deceived in the first place. In order to be deceived by something, he must be a thinking being, since thought is a requirement of being deceived. One cannot deceive a rock. Therefore, it makes no difference whether or not he is being deceived, since he could think he must exist: cogito ergo sum, “I think, therefore I am.” Yet, even this seemingly obvious claim has opposition in some philosophical circles. What this all goes to show is that absolute knowledge, if it is attainable at all, is incredibly hard. There may not be a perfect answer to give the, “It’s not proven,” crowd, but it is good to know that it isn’t necessarily because you or scientists have presented a faulty argument.

References

[2] Feldman, R. (2003). Epistemology (p. 17). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

[3] Maloney, Jonathan. “Black & White Thinking.” Intelligent Speculation. January 20, 2020.