Pseudoscience and The Need to Debunk Nonsense

In a world where sharing information is rampant, pseudoscientific claims have become a public health threat. This is further reinforced by algorithms and filter bubbles that personalize the user’s feed by detecting what has been shared or liked in the past. This might not be a problem for those trained in the sciences where skepticism, logical reasoning, and critical thinking skills are often applied, inoculating them against pseudoscientific advice that lacks any evidence of effectiveness. For others, these filters trap the user in a knowledge bubble and create a shield from opposing viewpoints.

In Pseudoscience: The Conspiracy Against Science [1], Kavin Senapathy writes:

“Too often, fighting pseudoscience outside the realm of research devolves into the pursuit of being right; battles fought with citations, corpses of hurt pride left to decay. And while truth is a thing of beauty, fighting pseudoscience isn’t necessarily about pedantry or self-righteousness, but progress and justice. To switch gears from science to confronting pseudoscience is a conscious back and forth, a tangible mind shift one must undertake consciously when called for. We must stay cognizant and check ourselves and our colleagues when we slip into holier-than-thou fact flinging.” (p. 442).

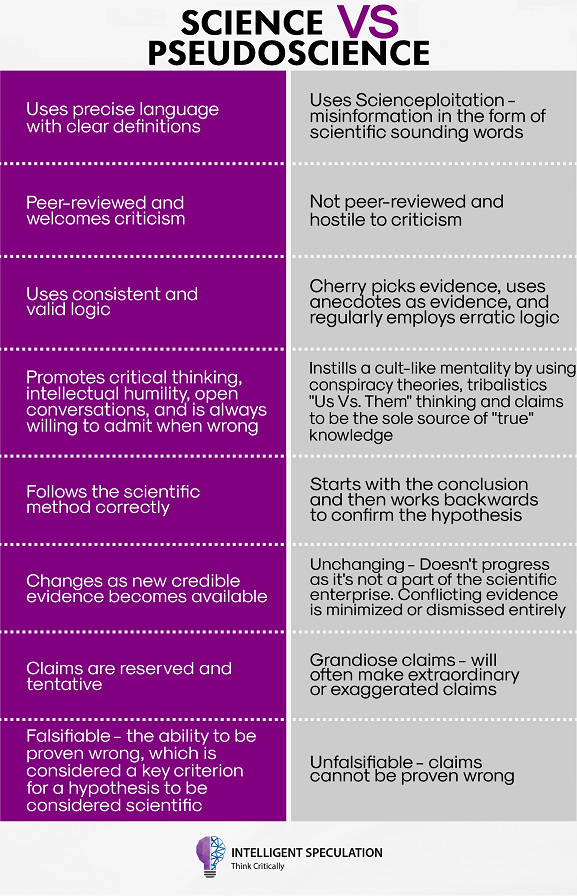

Pseudoscience is not bad science or fake science. Erroneous scientific results are not necessarily pseudoscientific. Bad science results in incorrect or unsound conclusions, usually drawn from valid premises, while pseudoscience presents sound conclusions based on invalid premises. The latter is intentionally deceptive in nature.

Why do experts devote so much time and effort to debunking pseudoscience?

Pseudoscience can kill

Pseudoscience and the general misunderstanding of science have always been present, but social media has facilitated its permeation into our everyday lives at a level that we’ve never encountered before. The internet is rife with “experts” sharing pseudoscientific medical treatments, therapies, supplements, and products which are often costly and may result in actual danger.

The medical literature documents many cases where alternative health care has led to direct harm. Using the Delphi method, an open access 2021 study [2] classifies the risks associated with alternative medical practices such as hypnotherapy, naturopathy, hydrotherapy, aromatherapy, and others. A significant number of direct and indirect harms are identified including major physical injuries or even death.

Promoted under the umbrella of “other ways of knowing”, traditional medicine (Ayurveda), complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), and integrative medicine have been endorsed by many homeopaths. Appealing to a different way of knowing is justified by the very fact that science does not know everything, exempting such practices from being subjected to rigorous scientific evaluation.

CAM is often widespread among cancer patients. A 2019 systematic review [3] shows that CAM can compromise the effectiveness of chemotherapy and other anti-cancer therapy, particularly when patients choose not to disclose their use of CAM to health professionals. Additionally, adhering to the naturalistic fallacy, cancer-preventing supplements, superfoods, and other miracle cures are promoted.

Integrative medicine appeals to patients as equal to conventional medicine, legitimizing it as a science-based approach. It is a multi-billion-dollar industry that has re-branded the terms ‘complementary’ and ‘alternative’, earning it respect as a non-pharmacological treatment. It includes a range of unproven and disproven interventions such as reiki, reflexology, as well as other metaphysical practices. In 2019, Florida [4] introduced a new law that forces health care providers to offer patients a non-opioid alternative to pain treatment, in an attempt to combat the opioid epidemic. Instead of suggesting scientifically investigated alternatives to pain management, health care practitioners must endorse and recommend pseudoscientific treatments such as acupuncture, chiropractic, and massage therapies despite the low-quality evidence to support such practices.

Pseudoscience is legitimized through marketing and profit

The monetization of pseudoscience has influenced public perceptions regarding key health issues. In the disinformation landscape, pseudoscience has taken part in what is referred to as the ‘attention economy’ and is tied to the rise of social media. Anyone can sell anything and profit from attention. In the competitive market, attention is a limited resource and a scarce commodity. Due to its dramatic nature, pseudoscience is the new currency weaponized to attract millions of consumers.

Misinformation in the form of seemingly harmless terms, such as renal fatigue, immune-boosting, detox, and others, has been repeatedly used to market pseudoscientific products. Timothy Caulfield, Canada research chair in health law and policy, refers to this practice as ‘scienceploitation’ [5] which has led to the formation and conservation of the wellness culture. Some doctors support wellness interventions, as long as they do not replace medical care. However, they know that when their patients report feeling better, it does not necessarily mean that they are better.

The Goop Lab, Gwyneth Paltrow’s Netflix series explores different unsubstantiated wellness approaches and advances pseudoscience in the marketplace. Goop [6] does not explain the science behind its content and absolves itself from accountability as a for-profit company under the disclaimer that its content does not intend to provide medical advice. The 250-million-dollar brand is part of the alternative medicine industry that markets pseudoscience in the wellness domain.

Pseudoscience is endorsed by celebrities

Celebrities normalize pseudoscientific behaviors. The celebrity-supported industry has reinforced ‘wellness’ products, pushing dangerous pseudoscientific practices and behaviors. Celebrities have access to the best health care; yet they tell their fans that it is a simple fix, probably available on their online shop.

Many celebrities including Jessica Alba, Oprah, Mayim Bialik, Michael Phelps, Doctor Oz, to list a few, have endorsed pseudoscientific ideas. The Kardashians have repeatedly promoted laxative teas, weight loss shakes, and diet lollipops. Tom Brady, an elite athlete, has his own theories. He attributes his health to 12 principles outlined in his 2017 book, The TB12 Method: How To Do What You Love, Better and for Longer. The book is a manual that details the 12 principles that Brady developed with his friend and business partner, Alex Guerrero, who has been investigated twice by the Federal Trade Commission.

The danger of pseudoscience endorsement by celebrities lies in their access to a huge audience. They directly influence how their followers understand health and how they embrace unscientific and even harmful treatments, behaviors, and products.

Pseudoscience fills an available niche

Every field of science has unanswered questions and gaps in our knowledge. While scientists view questions as an opportunity for new research, others fill the vacuum with pseudoscience, reminiscent of the God of the Gaps fallacy [7]. Pseudoscience has found its way to academia and conventional medicine because ambiguity is not embraced.

Miracle cures have exploited the gaps in scientific research. The spectrum of miracle cures [8] ranges from ineffective to deadly. Cannabidiol oil (CBD) is one example of a panacea miracle product that can allegedly treat a wide range of health issues including cancer, schizophrenia, insomnia, and anxiety disorders. The evidence [9] for CBD oil remains inconclusive, yet it is sold by hundreds of active producers and sellers in the market.

Oftentimes, people use the fact that conventional treatments fail or point to the rapacious business practices of pharmaceutical companies to justify pseudoscientific therapies. This mindset fails to realize that the shortcomings of the medical system do not justify embracing pseudoscientific treatments and unproven therapies as legitimate alternatives.

Pseudoscience persists

Pseudoscience tends to persist in the pool of common knowledge. It can effectively spread, even when corrected, debunked, or refuted, as in the case of the retracted paper that sparked the modern anti-vaccination movement. Historically, vaccines have saved millions of lives. Yet, the conspiracy theory that vaccines cause autism in children persists. Similar debates over climate change, GMOs, or fluoridation remain heated topics in the media. Many still think astrology is a science despite the absence of any evidence to support such claims.

Such stories help people tie information together and provide meaning to the scientific jargon that is often misunderstood. Stories connect people through shared experiences. Even after corrective information has been received, misinformation and conspiratorial thinking continue to influence people’s thinking.

Pseudoscience mimics some facets of science while fundamentally contradicting the scientific method. It can be challenging, particularly if one does not have a solid background in science, to understand or interpret scientific results. One reason is that pseudoscience shares the ‘surface properties’ [10] of science, but not its ‘depth characteristics’ such as verifiability, falsifiability, and progressiveness. This has obscured the line of demarcation between science and pseudoscience.

Conclusion

Highlighting pseudoscience, explaining why it is inherently faulty, and assisting people in distinguishing science from pseudoscience is more crucial than ever. The infodemic the world is experiencing demands standing up for scientific truth. Sadly, opinions and anecdotes are valued more than well-established results when it comes to evaluating assertions.

While pseudoscience masquerades as science, it must be debunked at every chance. Debunking pseudoscience indirectly serves a more fundamental purpose: it emphasizes what the scientific process really is.

References

[9] Hazekamp, Arno. 2018. “The Trouble with CBD Oil.” Medical Cannabis and Cannabinoids 1 (1): 65–72.